We are fortunate to live in such a beautiful place, as Oregon boasts an expansive network of waterways that captivate Oregonians and visitors alike. These incredible resources provide us with many excellent and diverse opportunities for boating. However, it is important to remember that in addition to recreation, these waterways also play an integral role in supporting biodiversity and the overall well-being of our state.

We are fortunate to live in such a beautiful place, as Oregon boasts an expansive network of waterways that captivate Oregonians and visitors alike. These incredible resources provide us with many excellent and diverse opportunities for boating. However, it is important to remember that in addition to recreation, these waterways also play an integral role in supporting biodiversity and the overall well-being of our state.

Today we are faced with escalating challenges posed by climate change and increasing human activity. With more people sharing our waterways than ever, and in some cases with less water than has previously been available, our negative impact on these natural areas is growing. To minimize this, we who love our waterways need to embrace environmental stewardship and be aware of the impact we have. If we truly appreciate and love these places, then it is our responsibility to treat them with care and protect them. If we do not, they will not always be there for us to enjoy.

What is environmental stewardship?

There are several definitions used for the term, so as an experiment, I asked Open AI’s ChatGPT to explain environmental stewardship in 50 words or less, and it wrote, “Environmental Stewardship is responsible management of natural resources and ecosystems to ensure their health and sustainability, balancing human needs with environmental protection through conservation, preservation, sustainable practices, and awareness.” ChatGPT only needed 29 words, and that’s an accurate and concise definition. But it is also generic and difficult to engage with, so we will try to do a little better. What do those algorithmically precise words really mean for boaters? What do we as humans really need to do to be better stewards of the water we love so much?

A good start is to begin thinking about our own impact. Everywhere we go, we have some kind of impact. Walking down a sidewalk we leave tiny amounts of our shoes behind on the pavement, we change the composition of the atmosphere around us just by breathing, and most people need to pee. Having no impact is impossible for any living thing that visits an environment. The best we can really do is pay attention to how we may be negatively affecting the environments we visit and try to minimize this. This is a responsibility that we all must share — one piece of trash in the water doesn’t seem like a lot, one plant destroyed in a riparian zone is just one plant, but they add up.

For boaters, environmental stewardship means recognizing that water is a resource we need to protect, both as a recreational area and a natural one that is valuable to us in many other ways. It also means that we need to be proactive in monitoring the impact we have and do our best to leave places the same or even better than we found them. Luckily, there is a program that is already well known to wilderness recreation experts and aficionados that can help point us in the right direction and provide a useful framework.

For boaters, environmental stewardship means recognizing that water is a resource we need to protect, both as a recreational area and a natural one that is valuable to us in many other ways. It also means that we need to be proactive in monitoring the impact we have and do our best to leave places the same or even better than we found them. Luckily, there is a program that is already well known to wilderness recreation experts and aficionados that can help point us in the right direction and provide a useful framework.

Leave No Trace

Leave No Trace is a national education program and organization. They work to educate people on how to protect the environment while experiencing it using evolving science-based principles. The author of this article is not certified or endorsed by this organization, however considering these principles in even a cursory way can benefit boaters and help to develop an ethic of environmental stewardship that resonates with our community. In the words of the Leave No Trace website “Although Leave No Trace has its roots in backcountry settings, the principles have been adapted so that they can be applied anywhere.” ( The 7 Principles of LNT ). For a better understanding and official representation of the Leave No Trace Principles, visit their website. The second part of this piece is a simple discussion of the seven principles the organization created and how they may help guide boaters to better protect their waterways.

The Seven Principles of Leave No Trace are:

1. Plan Ahead and Prepare

2. Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces

3. Dispose of Waste Properly

4. Leave What You Find

5. Minimize Campfire Impacts

6. Respect Wildlife 7. Be Considerate of others

Principle 1 – Plan Ahead and Prepare

To begin exploring how we can apply these principles as boaters it makes sense to start with the first principle because planning and preparation are already an important part of boating. Every boater worth their salt knows (or should) that we need to have a plan every time we go out. This means having an idea of the purpose, route, and length of the trip. It is also important to have a good idea of our own skill level and that of the people we are boating with the condition of all necessary equipment, and knowledge of the area we intend to boat.

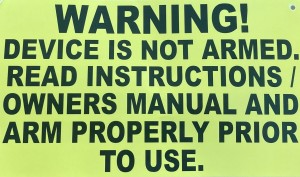

Planning well for a boat trip helps ensure that the trip will go well and be enjoyable for those involved. This leaves room for participants to consider what is around them and appreciate how they may be affecting it. It can be difficult to focus on conservation when one is simply trying to survive the day, and a good connection with nature can be difficult to form when it becomes threatened due to a lack of planning. Being prepared includes safety equipment and knowledge of the area as well as things like the proper bags or receptacles to haul out trash and food remnants or having a plan for using the restroom. In these ways and more, planning and preparation can make us better boaters and improve our ability to protect the environments we love while also preventing a considerable amount of misery.

Principle 2 – Travel and Camp on Durable Services

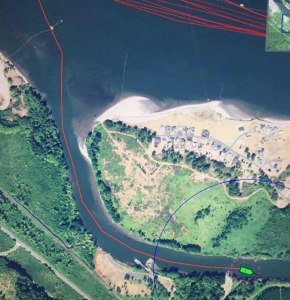

The next principle may be less obvious for boaters. Admittedly, water does have very similar physical properties everywhere. However, water is not the only surface we interact with while boating. Water access points are an important consideration as boats often need to transition between water and land. It is important to use established sites for accessing the water and remain on paved or prepared surfaces whenever possible.

The narrow strip of vegetation in the transition area between the water and land is called the riparian zone. This area is its own biome with unique communities of animals and plants that exist only within its narrow confines. It supports many species endemic to it as well as fish and animals in adjacent habitats, and far beyond. These unique communities are important and easily damaged and the relationships within them are very complex and the best way to protect them is to simply stay out. This means using established access points and boat ramps, as well as not setting up a camp or party spot in an area with vegetation. This principle is important for both motorized and non-motorized boaters. Motorized boaters should avoid actions like landing on shorelines with fragile vegetation or power loading at boat ramps as this further erodes the river bottom and damages the ramps. Nonmotorized boaters should avoid the temptation to venture into the riparian zone to launch their boats, or for any other reason, as even walking through these areas causes damage.

The narrow strip of vegetation in the transition area between the water and land is called the riparian zone. This area is its own biome with unique communities of animals and plants that exist only within its narrow confines. It supports many species endemic to it as well as fish and animals in adjacent habitats, and far beyond. These unique communities are important and easily damaged and the relationships within them are very complex and the best way to protect them is to simply stay out. This means using established access points and boat ramps, as well as not setting up a camp or party spot in an area with vegetation. This principle is important for both motorized and non-motorized boaters. Motorized boaters should avoid actions like landing on shorelines with fragile vegetation or power loading at boat ramps as this further erodes the river bottom and damages the ramps. Nonmotorized boaters should avoid the temptation to venture into the riparian zone to launch their boats, or for any other reason, as even walking through these areas causes damage.

Principle 3 – Dispose of Waste Properly

Perhaps the most obvious Leave No Trace principle is to dispose of waste properly. Nothing should be left in the water or on the shore that wasn’t there before, including trash, other human items, food scraps, and everything. The adage goes, “Pack it in, pack it out,” and that is exactly what we should do as boaters. Consider how to control and minimize the waste produced while boating. Proper planning should mean we have trash bags or containers on hand and a plan to carry and dispose of them. It may also mean bringing refillable water bottles and larger containers of water to reduce the possibility of tiny plastic bottles being lost overboard. Reusable food containers are also good for minimizing waste from food packaging that can often find its way into the water by accident. A well-prepared boater may even be able to leave the water cleaner than they found it by packing out a few extra pieces of litter that they didn’t bring out. Bring a pair of gloves and fill out that trash bag, keep the area you love beautiful, and know that you are an upstanding member of the boating community.

It is also important to consider human waste in our disposal plan. Knowing where shore-based restroom facilities are located or carrying an approved marine sanitation device onboard are acceptable options for number 2 waste disposal situations. The water and shore are not. For a number 1 waste disposal situation, shore-based facilities or marine sanitation devices are preferred, but when options are limited, it is better to deposit number 1 situations in the water than on shore, as the popular saying (that applies solely to number 1 situation disposal) goes “the solution to pollution is dilution.” Number 2 disposal situations must never be deposited in the water — brown trout are already an invasive species in Oregon.

Principle 4 – Leave What You Find

Principle four is also a little less obvious for boaters. It does, however, have some important lessons for us. Don’t take things from the environment that belong there. This includes fish, animals, plants, and even rocks. Of course, this does not apply to obvious situations like legal fishing, but be sure to follow all laws and best conservation practices while doing so.

Another good way to interpret this principle is to be aware of potentially invasive animals and plants that try to hitchhike on our vessels. Be sure to clean, drain, and dry any vessel when transitioning between waterways. Invasive species are incredibly harmful and they are often spread between states and bodies of water by unaware boaters who do not properly clean their equipment. This goes for motorized and nonmotorized vessels of any size, as even a kayak or inflatable SUP can carry invasive species.

Principle 5 – Minimize Campfire Impacts

First of all, don’t have a campfire on your boat. Boaters can use their vessels to access unimproved beaches and shoreline areas, as well as established sites that work much better for this. Most of us enjoy a good campfire and boating can provide some unique opportunities to have one. When starting a campfire, it is best to use an already established fire ring in an improved site. If in an unimproved area, portable fire pits and fire pans help to prevent scorched areas on the ground, contain the fire for safety, and allow for easier cleanup. Do not burn wood you find in areas where there are few trees because the environment cannot easily replace it and it may have an important purpose in the ecosystem. Also, bringing a metal container to pack out ashes can help to lessen the impact of campfires on natural areas.

Be aware of the fire danger in your area before starting a campfire and make sure that all flammable items and vegetation are well clear of it. Never leave a fire unattended and make sure it is dead out when finished. Fires can seem to be extinguished but still have hot spots capable of reigniting for days. To learn more about campfire safety visit Smokeybear.com, and please kindly ignore any similarities you may notice to the completely original title of this article.

Principle 6 – Respect Wildlife

Respecting wildlife is important for reducing our impact on the environment. Outside of hunting or fishing, wildlife should be viewed from a distance and never chased or disturbed. Getting too close can cause stress to wild animals. This can impact their behavior and in turn, impact the ecosystem in complex ways we are unable to predict. Give animals plenty of space when boating and avoid disturbing them with loud noises or quick movements. Never touch, feed, get close to, pick up, or hold wild animals. Observe quietly and  enjoy learning about their natural behaviors, as many are fascinating.

enjoy learning about their natural behaviors, as many are fascinating.

Following principle 3 and disposing of waste properly is an important way to respect animals, because keeping the environment clean contributes directly to their health. Of special note are human food scraps. Many people feel that it is ok to dispose of food scraps in the water or bushes, but this is wrong. Human foods that do not belong in the environment are also a form of pollution. An orange peel thrown into the bushes can seem like no big deal, but it does have an impact on the environment. Leaving human food scraps onshore and in the water can attract wildlife to areas frequented by people and lead to conflicts between them. This usually ends up meaning early death for the animals, also sometimes the people. Much like disturbing the animals, leaving food scraps around will impact their behavior and the entire ecosystem.

A good example is one observed many times by the author while working as a multi-day rafting guide. Use of riverside campsites by boaters with a poor ethic of environmental stewardship results in a regular supply of small food scraps being left in these camps. Not a lot, but enough. These food scraps attract rodents, which then become habituated and concentrate around these sites frequented by humans. The concentration of rodents itself can result in conflict with humans, but it also attracts their natural predators, in this case, rattlesnakes. The small food scraps that didn’t seem like such a big deal then lead to a significant increase in rattlesnake/human encounters, which are at best uncomfortable for both parties. Pack it in, pack it out…

Principle 7 – Be Considerate of Others

The final principle of Leave No Trace is to be considerate of others. In much the same way that preparation in principle 1 makes environmental stewardship more possible by reducing the stress of people in our own boat, being considerate extends this to other users of our waterways. Being upset or angry makes it difficult to focus on the environment since it takes up all our mental space. By being considerate of others, we extend them an opportunity to also be better stewards of our waterways.

Behaving badly or in ways that needlessly disturb the experience of others has its own negative impact on our waterways. Being considerate can help to foster a sense of community that will help all of us to focus on protecting the areas we are so lucky to have.

Be a Steward of the Water

By using these principles to guide us in practicing environmental stewardship, boaters can protect the waterways we all enjoy. It can seem like these individual acts won’t have much of an effect, but like the negative impacts we can have on natural areas, the positive acts also add up.

People imitate each other and affect each other’s behavior in ways that we don’t realize. Making the effort to be a better steward of the water by treating others and the environment with respect can inspire others to do the same. In this way being a steward of the water not only helps by directly protecting our waters, but also by inspiring others to value and respect our waterways. Even an act as simple as picking up a plastic wrapper that you didn’t put there could inspire someone else to do the same. There are effects of our behavior that extend far beyond what we get to experience.

So take the time to protect the places that we love, be proud of your efforts, and know that you can be a hero to others, the environment, and yourself by choosing to be a steward of the water. Happy boating.

About the Author